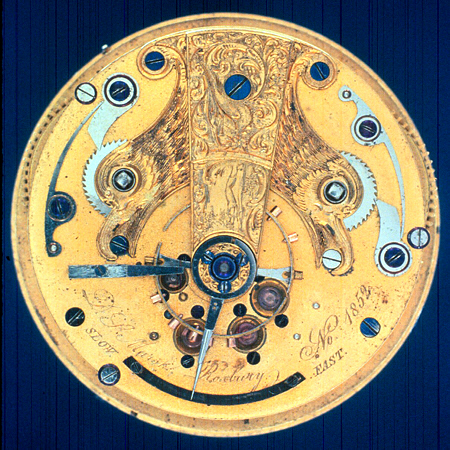

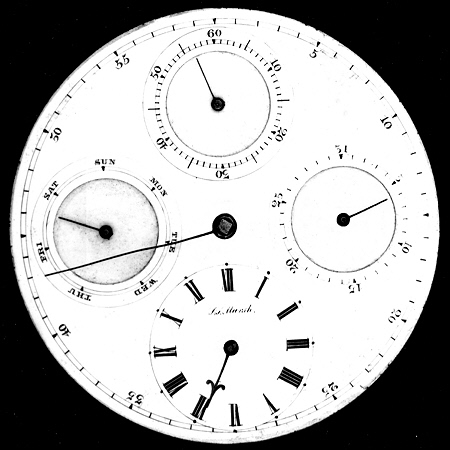

Origins of the Waltham Model 57Prefaceby Ron PriceCopyright © 1995-2019originally published 2005 by NAWCC as Supplement No. 7 No, this is not a Model 57 pocket watch. It is a model of an eight-day watch that Aaron Dennison, renowned cofounder of the American watch industry, initially wanted to produce. This approximate 22-size watch with twin barrels, and a second identical mate, were made by brothers D.S. Marsh and O.B. Marsh under the direction of Mr. Dennison. Although a good timekeeper, it unfortunately proved too expensive to manufacture according to Dennison’s business goals; otherwise the Model 57 and a century’s worth of mechanical watches to follow would have been substantially different. The Marsh brothers were allowed to keep their model watches for themselves, so the elaborate embellishments seen here (including a calendar dial) might have been added later to the prototype or perhaps even to a different movement. The number 1852 on the watch probably indicates when the timepiece was made. The D.S. Marsh watch, adorned with nationalistic sharp-eyed eagles, is not only artistic, but represents the visionary talents of its creators and the founders of the watch industry. For this reason the author chose the Marsh watch to be pictured on the cover of his monograph. For more information on the Marsh watches, see article by James West, Dennison’s Eight-Day Watches - The Titanic Connection, NAWCC Bulletin, October 1997, page 563. The photographs of the D.S. Marsh movement and dial were graciously provided by the Henry Ford Museum & Greenfield Village in Dearborn, MI.

It works. Another trick learned from the master watchmaker. The master was the late Pasquale (Pat) Caruso who learned his vast number of tricks of the trade during his thirty years at the Waltham Watch Company and 60-some years, all told, in the business. The trick that Pat told me was that I could get additional timing regulation from the hairspring on my old P.S. Bartlett by removing the inner regulation pin and bouncing the hairspring off the outer pin. This was a nice expedient solution until I could get the hairspring replaced. I needed this extra adjustment because I had broken the hairspring off at the point where it enters the anchor on the plate (the spring is not studded on these early “Walthams”). All I wanted to do was improve the beat. Thick fingers and amateur skills were probably the main culprits, but the hairspring was undoubtedly weakened by the many repinings when the balance was previously removed. I was already annoyed by having to remove the dial to get at the mainspring click. This watch clearly was not designed with the repairer in mind. This P.S. Bartlett served me well for years. It has an attractive Appleton Tracy & Co. case and dial. It keeps good time, but I became disenchanted with it the last time I banged up the hands when resetting the time from the front dial key set. I do not know why the founders of the Waltham Watch Company could not have designed the watch with the key set in the back. I guess it was easier to manufacture, the case was cheaper and it was the popular English style of the time. Another design problem for the repairer is that on these early "Walthams" the hairspring is mounted between the balance arms and the roller table. This was changed in the next models with the spring located above the balance arms, but it was left in the lower position on the Model 57 for many years. Another thing I find interesting is that references say the escape wheels on the very early watches had pointed ratchet teeth, but later versions were designed with a club tooth shape. However, most of my older Model 57s have escape wheels that look more like the ratchet type with squared-off ends. These issues were puzzling to me, and I could not find much written about them. Then I began coming across pieces of conflicting data. In particular, I have a P. S. Bartlett watch with a serial number in the two thousands. I also have a Dennison, Howard & Davis (DH&D) watch with a three thousand serial number. I assumed the P. S. Bartlett was older since it had a lower serial number. However, according to a book on the production records of the American Watch Company [reference 1], the P.S. Bartlett was made after the DH&D watch. The game was afoot! I began digging deeper and taking notes. I eventually solved my mystery with the serial numbers, and did find explanations for most design questions. However, many historical and technical questions remain. For example, did the Boston Watch Company (BWCo.) or Appleton Tracy & Co. (AT&Co.) produce any unmarked movements as a reference suggests? How many DH&D watches of the Boston Watch Company existed unsold at the time of the bankruptcy auction in 1857, and did they go with Rice (Howard & Rice Co.) or remain with Robbins at AT&Co.? How many DH&D ebauches were finished and sold by AT&Co.? Why were the Howard & Rice movements and the first AT&Co. movements 16 jewels while the DH&D movements were 15 jewels.? When was the pointed tooth escape wheel changed to the blunt-end tooth on the Model 57? When was the full club tooth escape wheel introduced? When was the hairspring sprung over on the AT&Co. grade watch? Was quick train actually ever employed on the M57? I think searching for these kind of answers gives collecting an added dimension and makes collecting more challenging. To me the joy of collecting is not just in the owning, but in the discovery of something different or something new. I soon learned that many other collectors feel the same way, and through their encouragement my note-taking became more formal. Answers to many questions were obtained from analysis of historical documents, including unpublished records. To this end, one of my objectives is to provide a comprehensive reference book on the subject. So while this monograph is in many respects another history paper on the Waltham Watch Company, I tried my best when I make statements about something I tell you where I got them. Answers to more questions can be found by direct observation. To this end I set out to record observable features of the Model 57 and its predecessors. Definite conclusions generally cannot be made from one or two sample movements, but seeing the data in tabular form from many movements, a clear pattern is unrefutable evidence. Data tables are provided at the end of the paper for each signature (grade) movement. Data were obtained personally and from reference sources, but this project would not have been possible without the generous assistance of a large number of people. Indeed, more items were requested to be tracked as the project evolved, which accounts for sparse columns in the tables. This project is actually open ended and on-going. Contributions are always appreciated. I would like to thank the following people for their help and for sharing with me their knowledge of the early Walthams (many additional people contributed who prefer to be anonymous or have not given me permission to publish their name). My apologies for missing names I forgot to write down.

! from Australia !! from Brazil * from England ** from Canada Appreciation is also extended to (references are accurate at the time for when data was provided):

Cautionary comments on pictures herein: |